|

| (Left to Right) Dennis Wilson, Laurie Bird, and James Taylor, with a 1955 Chevrolet 210 Hardtop, from Monte Hellman's Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) |

It is easy to admire Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, Reyner Banham’s 1971 inspired take on Los Angeles, once thought of as the most elusive of American cities. This book has a lot to answer for, especially in the way it expands the way we analyze and study the contemporary city. Indeed, it is hard to imagine this book existing independent of William Cronon’s rigorous spatial history of Chicago, born under the occluding signs of Karl Marx and Walter Christaller, or even Lars Lerup’s Duchamp-fueled fever dream of Houston, one that may leave you seeing skyscrapers as chocolate grinders and marine layers as “zoohemic canopies.”[1]

What in the hell have I just read? you may ask yourself, and this is why it is even easier to love Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles, the 1972 BBC short documentary film that gives Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies visual grist for the literal mill and shows an avuncular, perhaps slightly stoned Banham taking a motorized gander around the so-called “Metropolis of the Future.” Now we know what the Plains of Id, Autopia, and Surfurbia look like, thank you very much. This paean to the technologically-mediated modern landscape resonates in an age when our primary means of knowing a city is not through the writings of a Cronon or a Lerup.

(And in the case of Los Angeles, the Thomas Guide is all but an antediluvian spiral-bound sheaf of grids and coordinates, gone by the way of the Dodo, Great Auk, or Sabre-Toothed Cat.)

Our reliance on smart phones and tablets for urban wayfinding is so common that it deserves only the most fleeting of mentions. Interfacing has become the new wayfinding, one brandishing its own peculiarities. The female voice on the Google Maps app can be too bossy, imploring you, “In 500 feet, TURN RIGHT.” Can we actually measure distance while staring ahead over a steering wheel? Indeed, that voice immediately takes me back to my eighth grade typing class, especially those moments when my teacher would demand that we type sentences, clackity-clack, in time to a record playing a kind of Lawrence Welk-ish champagne music with firecracker snares. Her voice was mellifluous, but not too much, barely containing a hair-trigger snarl that would uncoil the very instance you fucked up your keystroke. The female Google Maps voice is more forgiving—not as much as Scarlett Johansson's in Spike Jonze's Her (2013)—even while insisting that you turn around as she quickly reroutes your itinerary.

Banham’s guide to Los Angeles is the “Baede-kar Visitor Guidance System,” a technology that straddles centuries, at once evoking Karl Baedeker’s travel guides from the 19th century, as well as guidance systems for modern intercontinental ballistic missile—two completely different ways of “knowing” a city, one as destination, the other as target. The female voice issuing from the molded speakers of the “Baede-kar Visitor Guidance System” is more Siri-like and soothing, but lacking the latter’s notable cheekiness. It is a shame that we do not pay more attention to the “Baede-kar,” its voice, or for that matter, the various technologies on display in Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles. They create their own constellations, each gizmo or doohickey bringing its own origins and relationships to bear, making connections in time and space, revealing something about our own mediatic situation in the process.

Take, for instance, the opening scenes from Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles. Note how Banham, tweedy, with newsboy hat and giant sunglasses, walks from the Arrivals terminal at Los Angeles International Airport and boards a 1970 Pontiac Grand Prix Hardtop. And like in other films of this time, we immediately associate the driver with his car, each becoming the other. The Grand Prix Hardtop is a close cousin to the 1970 Pontiac GTO Judge that Warren Oates drives in Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), vying for the attention of consumers of American Muscle, especially those who took a fancy to the 1968 Dodge Charger or Mustang GT 390 in Peter Yates’ Bullitt (1968) (the last, of course, doing multiple star turns throughout San Francisco streets, Steve McQueen at the helm), or even the 1970 Dodge Challenger in Ricardo C. Sarafian’s Vanishing Point (1971). Jimmy Kowalski (Barry Newman), a Vietnam veteran, now driver on the professional and demolition circuits, is behind the wheel, although all the action scenes feature legendary stunt driver Carey Loftin, who wears a wig over his crash helmet.

Singer James Taylor (the “Driver”) drove the 1955 Chevrolet 210 in Two-Lane Blacktop. It had a glass nose and Plexiglas windows. It would make an encore performance as Bob Falfa’s (Harrison Ford’s) ride in American Graffiti (1973), now wearing a fiberglass body, a M22 Muncie transmission (known to Hot Rod enthusiasts as the “Rock Crusher”), and gear rings and pinion gears (in 4.88 ratio) repurposed from an Oldsmobile. Those who purchased More Fun In the New World (1983), the fourth studio album by Los Angeles punk-a-billy scenesters X, will recall a similar automotive inventory in “The New World,” the album’s opening track, when bassist John Doe and singer Exene Cervenka map out the various parts of an car assembly: “Flint Ford Auto, Mobile Alabama / Windshield Wipers, Buffalo, New York / Gary, Indiana, Don’t Forget the Motor City ...”[2] In Two-Lane Blacktop, the “Driver’s” “Mechanic” was Dennis Wilson, better known as the drummer for The Beach Boys. One of their most beloved songs is “Little Deuce Coupe” (1953), with Brian Wilson singing, “She's ported and relieved and she's stroked and bored. / She'll do a hundred and forty with the top end floored.” [3] The Chevy is vain, thinking that the song is about her.[4]

A brief inventory of other sonic ephemera comes to mind. We can imagine these playing through FM album-oriented rock (AOR) stations, 8-tracks, and even cassette tapes and compact discs, not so much instances of car and driver melding, but of driver and music interfacing the same way as Banham and the “Baede-kar,” coursing sonic maps for our technological predicament, from Daniel Miller (aka The Normal) droning “Hear the crushing steel / Feel the steering wheel” in “Warm Leatherette” (1978), to Steve Kilbey, lead vocalist and bassist for The Church, singing, “Cut your life into the steel / Take your place behind the wheel / Watch the metal scene just peel away” in “Chrome Injury” (1981), or Duran Duran lead singer Simon LeBon crooning “And the droning engine throbs in time / With your beating heart” in “The Chauffeur” (1982): all, in some way or another, derived from J.G. Ballard’s Crash (1973), itself a paean to the “Little Bastard,” the Porsche 550 Spyder, which, on the afternoon of September 30, 1955, flipped end-on-end as it was avoiding an oncoming 1949 Ford Tudor, killing James Dean, making him into a cult American figure almost instantaneously.[5]

|

| Variants of "Moore Computer": (Top) the "Baede-kar" navigation system from Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles; (Bottom) Title card to Sydney Pollack's Three Days of the Condor (1975) |

As for the "Baede-kar," it is an 8-track tape, obviously. American car manufacturers started introducing 8-track players as luxury feature upgrades by the mid-1960s, so it is not a surprise that Banham's Pontiac Grand Prix has one in the center dash. As for the technology, it was a product of the convergence of the aviation, automotive, and telecommunications industries. One of the inventors of the 8-track was Bill Lear, famous for the private jet bearing his name. The primary financial backers for the "Lear Jet Stereo 8" cartridge player were Ford and General Motors, with RCA, Motorola, and Ampex manufacturing the players and tapes. The typeface visible on the front of the “Baede-kar”appears as a derivative of “Moore Computer,” an E-13B Magnetic Ink Character Recognition (MICR) font created by Steven Moore in 1968, and yet its stylish, italicized appearance suggests a combination of Data 70, designed by Bob Newman in 1970, or Westminster, a machine-readable typeface designed by Leo Maggs for Westminster Bank Limited (it is still used to print routing numbers on personal checks).

|

| Print ad for Lear Jet Industries'"Lear Jet Stereo 8" |

The 8-track player, the most advanced technology in Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles, was in fact quite limited. Stereo and quadrophonic sound came at an expense: users could not fast forward or rewind. It was a read-only medium, too. Playing an 8-track tape was therefore all too presentist, rooted in the then-now, preserving the music in real-time, moving forward, only to begin again, ensnaring the listener in an infinite aural loop—almost. Recall that an 8-track cassette was split up into four "programs" of equal length, and to find to a song earlier or later in the album, a listener had to guess where in the "program" the song ahead or behind would be and press the "program" button at the appropriate time. It took crackerjack guesswork and an intimate knowledge of the music on the album. And yet the program button switch only allowed the tape to advance forward time, from 1 to 2, 2 to 3, 3 to 4, and 4 to 1, until it reached the beginning.

Though technically a dead medium, the 8-track player is resuscitated as another technology in Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles, cloaked in the vestments from a near-future. It becomes the zero vector for a host of other technologies we know today, from dashboard-mounted Tom-Toms, to the plastic thingamajigs we attach to the air conditioning vents so we can look at Google Maps on our phones while we drive. The 8-track cassette is the skeleton key that opens up environments for us to read, consume, and exhaust. Its spatial and temporal constraints mirror our own, as we must always locate our own futures and pasts, our physical presence in relation to our temporal present. The same goes with the “Baede-kar,” as Banham would have no choice but to let the 8-track move forward and surrender to the spatial narrative, always keeping his eyes on the road. Too bad he did not have a Thomas Guide.

|

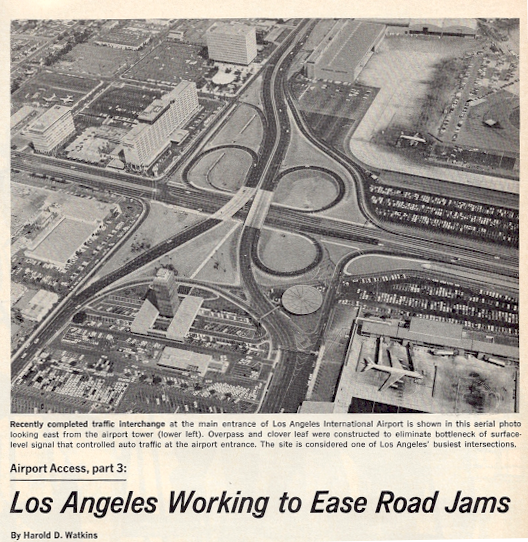

| Aerial view of Los Angeles International Airport, from Aviation Week & Space Technology, 14 November 1966 |

That the 8-track was born of the aerospace industry is again significant, and here we find novelist Thomas Pynchon, in Los Angeles, writing about the aftermath of the Watts riots, invoking airliners, perhaps not unlike the scene that would greet Banham when landing at LAX in 1972:

Overhead, big jets now and then come vacuum-cleanering in to land; the wind is westerly, and Watts lies under the approaches to L.A. International. The jets hang what seems only a couple of hundred feet up in the air; through the smog they show up more white than silver, highlighted by the sun, hardly solid; only the ghosts, or possibilities, of airplanes.[6]This is by way of a piece he wrote for the The New York Times Magazine, published on June 12, 1966, entitled “A Journey Into the Mind of Watts.” Like the 8-track “Baede-kar,” or even the Porsche 550 Spyder, the passenger jet is a technology indelibly woven into its own impermanence.[7] The metal tape heads on the 8-track wear down as aircraft and cars turn into corroding hulks of unrecognizable alloy. No wonder the jets on approach to LAX appear not as airplanes, but as images of airplanes, a moment causing Pynchon to remark on the “image-ined” city that is Los Angeles:

What is known around the nation as the L.A. Scene exists chiefly as images on a screen or TV tube, as four-color magazine photos, as old radio jokes, as new songs that survive only a matter of weeks. It is basically a white Scene, and illusion is everywhere in it, from the giant aerospace firms that flourish or retrench at the whims of Robert McNamara, to the "action" everybody mills long the Strip on weekends looking for, unaware that they, and their search which will end, usually, unfulfilled, are the only action in town.[8]The whiteness of the sky, the whiteness of the jets, the whiteness of the “Scene”: testaments of how our grandest aspirations originate in a degree zero of color, casting a harsh light on our own misdeeds and misreadings. And that is perhaps why something like the 8-track tape, miscast as an advanced technology, flawed, imperfect, demands a closer look, for it causes us to be all too aware of the imperfections in our intractable, unavoidable present. If listening to an 8-track preserves us in the amber of our own time, then ours in an existence in which we continuously yearn for other media—pictures, sounds, words—that afford us the illusion of looking forward and backward.

|

| Los Angeles, 1965: Phyllis Gebauer with Thomas Pynchon, in the back, flashing a peace sign behind a door. (Source: Los Angeles Times) |

Is this not the way we read? We engage, as Italo Calvino urges in If On A Winter’s Night a Traveler (1979), “in pursuit of all these shadows ... those of the imagination and those of life.”[9] Perhaps this is why fantasy novels like Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle (1962) or Alan Garner’s Red Shift (1973) all look to things from bygone eras as a way to locate our own time and space. In the case of Dick’s novel, the provenance of a supposedly fake Colt revolver takes center stage, causing its buyer to experience the world as it was in 1962, and not the alternate history that drives the novel’s plot—one in which Germany and Japan win the Second World War and divide the United States into occupational zones. And in Garner’s Red Shift, the reader is actually experiencing three timelines—one in Roman antiquity, another during the English Civil War, and a final, contemporary one—all marked from the “point of view” of a stone axe found embedded in a chimney in Southern Cheshire, England. If Reyner Banham famously needed a car to “read Los Angeles in the original,”[10] then perhaps the only way to do so was with the help of a flawed technological artefact. Perhaps this is why in writing about writing about reading the city, the only recourse is to write topologically across different times, grasping at references of objects from those eras, from cars, the parts of cars, to images, sounds, and finally words.

At least that’s what I have done. The references are mine, but they can be yours too. For writing on a warm weekend in Indianapolis, Indiana in 2015, this is how I have come to finally know Los Angeles, this city on the other side of the world, one that was my home from 1999 to 2005. For in writing about writing about reading the city, and reading about writing about writing, I only have done what we all do. We try to explain the here and now, and while doing so, we produce a reader’s guide to our own reader’s guide.

__________________________

Notes

[1] I am referring here to two books that, in addition to Banham’s Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, have shaped my own understanding of cities. There is, of course, environmental historian William Cronon’s Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York: W.W. Norton, 1992), which relies on German geographer Walter Christaller’s contributions to central place theory, as shown in texts like Die zentralen Orte in Süddeutschland (1933). My first understanding of the architectural “understanding” of a city came via Lars Lerup, After the City (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2001). A version of Lerup’s Duchampian take on Houston also appears in “Stim and Dross: Rethinking the Metropolis,” Assemblage 25 (1994), 82-101.

[2] John Doe and Exene Cervenka, “The New World,” on More Fun In The New World, Elektra Records, 1983, 33 1/3 rpm.

[3] Brian Wilson and Roger Christian, “Little Deuce Coupe,” on Little Deuce Coupe, Capitol Records, 1963, 33 1/3 rpm.

[4] Not-so-veiled reference to Carly Simon, “You’re So Vain,” on No Secrets, Elektra Record, 1972, 33 1/3 rpm, especially the refrain, “You’re so vain / You probably think this song is about you.” Simon was married to James Taylor when she wrote the song.

[5] The songs are as follows: Daniel Miller, “Warm Leatherette,” on T.V.O.D./Warm Leatherette, Mute Records, 1978, 45 rpm (the song would be made famous by Grace Jones in 1980); Steve Kilbey, “Chrome Injury,” on Of Skins and Heart, EMI Parlophone, 1981, 33 1/3 rpm; and Duran Duran, “The Chauffeur,” on Rio, EMI/Capitol/Harvest 1982, 33 1/3 rpm.

[6] Thomas Pynchon, “A Journey Into the Mind of Watts,” The New York Times, June 12, 1966, https://www.nytimes.com/books/97/05/18/reviews/pynchon-watts.html.

[Author's Note: This is a version of the essay I wrote for the exhibition, Now, There: Scenes From the Post-Geographic City, curated by Tim Durfee and Mimi Zeiger. The show is currently on display at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California, and in December, will move to the Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture in Shenzen and Hong Kong. For more on the exhibit, go here, or visit Art Center's Media Design Practices program site. Special thanks go to Mimi for asking me to be part of this exhibition]