![]() |

| Gaston Tissandier's and Jacques Ducom's aerial photograph, from Hippolyte Meyer-Heine, La photographie en ballon et la téléphotographie (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1899), 4. |

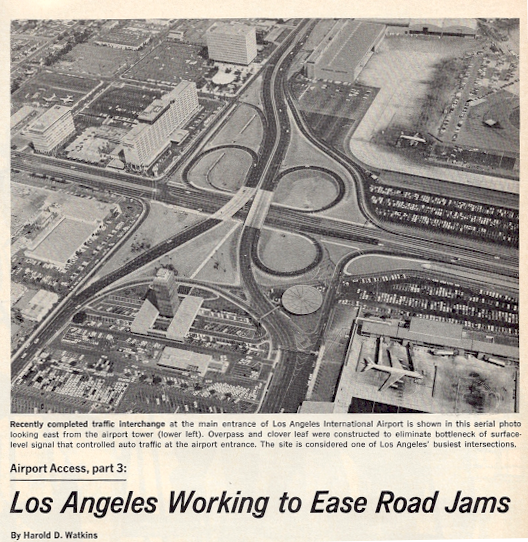

On 19 June 1885, the Parisian scientist and aeronaut Gaston Tissandier, with his assistant Jacques Ducom, ascended by balloon from his “atelier aérostatique” at Auteuil and flew towards the Seine. At a height of 605 meters, directly over Île Saint-Louis, the two men pointed a camera downwards and took a picture of the city below. The resulting photograph was not thrilling like Nadar’s 1858 image of the Place de l’Etoile. Yet this image, taken at an oblique angle, is as important for its unprecedentedness as for its sense of the balloon’s vertiginous altitude. It is a view that anticipates a new realm of seeing and understanding urban spaces below. If, as art historian Vittoria di Palma suggests in her brief study of micro- and macro- views as forms of knowledge, “aerial photography and urban representation were joined from the very start,”[1] then Tissandier’s and Ducom’s image presents an important moment in this lineage. Here, the city appears with remarkable clarity and precision. Public and private spaces are easily distinguished. The waters of the Seine emerge as a watery blanket rippling with waves. More importantly, this photograph gives a sense of the form of the city. Much like the crisp outlines defining a flotilla of boats plying the river’s waters, here, the city appears not only defined, but also designed: the way in which the Pont Louis-Philippe, for example, connects the tip of Île Saint-Louis to the bank of the Seine, is clearly visible in the photograph. Writing in 1899, the military engineer Hippolyte Meyer-Heine hailed the photograph for its “perfection” and as proof that aerial photography would surpass terrestrial photography as a method for depicting the urban environment.[2]

Aimé Laussedat, the director of the Conservatoire des Arts et Metiers, included a version of the image in his important text, Recherches sur les instruments, les méthodes et le dessin topographiques (1898). Laussedat (1819-1907) was an influential figure whose career straddled various disciplines. As an active and modernizing voice within the Conservatoire, he published dozens of articles and books that introduced important innovations and techniques in geography and cartography. Before this, he was a highly decorated military officer and surveyor. While Engineer-Commander of defenses for the Left Bank during the Franco-Prussian War, Laussedat was in charge of creating highly detailed maps of cities and towns and would eventually be responsible for mapping the new boundaries between France and Germany after the 1871 Treaty of Frankfurt. He would, however, gain his greatest recognition for his contributions to the nascent field of photogrammetry—a body of techniques and methods of using terrestrial photographs for the creation of topographic maps.[3] In 1862, he was hired by General General Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero, the President of the International Geodetic Association, to apply these photographic techniques in creating a detailed survey map of Spain.[4] Laussedat is often credited to be the “Father of Photogrammetry,” yet his importance to this post lies in two interconnected realms. First, he derived a kind of photogrammetry from aerial photography, which in turn became the basis for a system by which cities could be measured from the air. Second, this technique would mark one of the first instances where photography would be directly applied to the design and construction of buildings.

![]() |

| Ducom’s and Tissandier’s aerial photograph, compared to a map of Paris, from Aimé Laussedat, Recherches sur les instruments, les méthodes et le dessin topographiques (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1899), 82-83. |

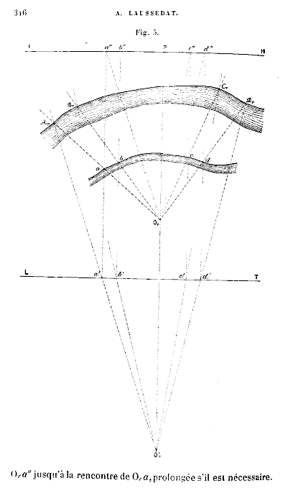

To illustrate the importance of aerial photography, Laussedat placed Tissandier and Ducom’s photograph alongside the corresponding section from the official map of Paris. The latter image appears almost identical to the aerial photograph, an indication that photographs made from balloons or kites could yield similar results as those using ground surveying techniques. Yet for Laussedat, these aerial methods were fraught with problems because in some instances, unpredictable winds and turbulent air could cause a camera aboard the balloon or kite to wobble and vibrate—these were circumstances that could compromise the all-important perpendicular to the ground plane necessary for accurate vertical photographs. This was a vital consideration for two reasons. On the one hand, a difference between a perfectly horizontal and a slightly tilted ground plane could turn an image that would otherwise be suited for measurement into a standard architectural plan.[5] On the other hand, Laussedat’s remark admitted to how air could, in a sense, resist the practice of accurate measurement. These two comments on the relationship between the city-as-photographed and city-as-measured not only depend on a different understanding of air than before, but they also share a convention: a variant of the aerial line which I call a photogrammetric line.

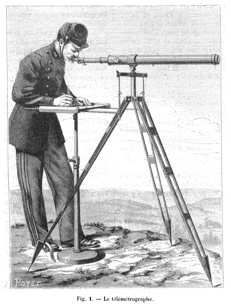

![]() |

| Émile Wenz’s kite photograph, from Laussedat, “Recherches sur les instruments, les méthodes et le dessin topographiques: méthodes et instruments de dessin. Innovations principales proposées,” Annales du Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, publiées par les professeurs, Vol. 4, No. 3 (1902), n.p.. |

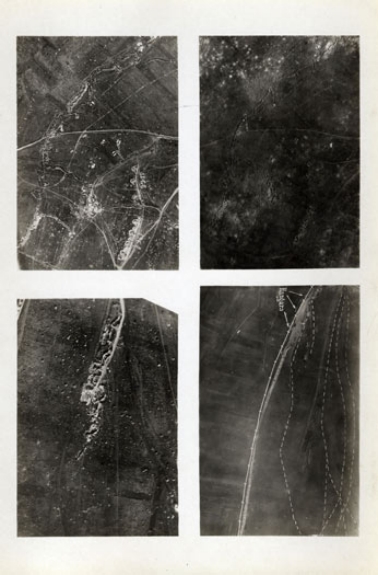

A photogrammetric line is a hypothetical line that travels in the air from a photographed or measured subject to the lens of a camera or sighting device. A good example is an image taken by Émile Wenz appearing in a 1902 issue of the Conservatoire’s Annales. Here, on an aerial photograph of the hospital at Berck-sur-Mer near Calais, a web of dark lines extend from the building façades and seem to move through three-dimensional space to an imaginary, hovering point—a point in the middle of the air corresponding to the location from which a kite-mounted camera would be suspended.[6] The photogrammetric line also travels in the reverse direction, from eye to subject.[7] It finds its origins in perspective treatises, as illustrated by Alberti’s notion of the “centric ray,” which Anthony Grafton identifies succinctly as “the ray that covered the distance between the center of the eye and that of the object.”[8] Yet the line could also appear to be material. This can be seen in Abraham Bosse’s “Les perspecteurs,” an engraving from his influential Manière universelle de M. Desargues (1647-1648) showing three painters constructing perspectival views.

![]() |

| Abraham Bosse (1602/4-1676), “Les perspecteurs,” engraving from Manière universelle de M. Desargues pour pratiquer la perspective par petit pied, comme le géométral (Paris: 1648). |

Here, the rays emanating from the object to the eye appear as tangible strings, a convention equating tautness with rectilinearity as evidence of “the last trace of materiality before the immateriality of pure geometry takes over from the visible.”[9] With the arrival of photography in the 19th century, such lines could also operate as a metaphor for distance.[10] Imagined yet rational, a photogrammetric line moors the theoretical to the practical.[11]

In order to understand the role that photogrammetric lines would have to play in this genealogy of aerial lines, it is important to first go back to Laussedat’s Recherches to consider his mode of writing as well as his literal and figurative point of view. Like Étienne-Jules Marey’s use of important precedents in the history of graphic representation for his La méthode graphique (1885), Laussedat’s multivolume text uses historical examples in order to legitimize the practices of geodesy and topographic measurement and does so through a strategic use of images. The opening chapter, a veritable “Historical Overview of the Instruments and Methods” of topography, makes its architectural origins very clear. Laussedat began with Claude Perrault’s reconstruction of Vitruvius’ chorobates, a kind of water level used for planning aqueducts.[12] The chorobates was a rather simple instrument comprised of a two legs supporting a plank with a trough cut through its middle. A surveyor filled the trough with water and then sighted a level line only when the water stayed within the trough. At first, Laussedat’s own predilections veer towards the contemporary. He claimed, perhaps unfairly, that the chorobates lacked the precision offered by more modern techniques and instruments such as diopters.[13] Recalling Laussedat’s original concern that aerial photography techniques may be sacrificed due to wind conditions impeding the sighting of a proper line perpendicular to the ground, it is worth noting that this too was one of Vitruvius’ chief concerns.

![]() |

| Engravings of Demeliorem using a graphometer, from Laussedat, Recherches sur les instruments, les méthodes et le dessin topographiques, 62. |

In his section dealing with the chorobate, Vitruvius admitted that the wind may interfere and prevent a “clear reading because of its motions.”[14] Laussedat’s emphasis on the clear reading of lines culminated in a survey of astronomical and geodetic instruments from antiquity, and he eventually settled on the first instance of a sighting line used for architectural purposes: an engraving from Joannes Demerliorem’s Quadrati geometrici usus, geometricis demonstrationibus illustratus (1579) of a surveyor using a geometric square to measure the height of a tower.

Like other engravings from the Renaissance used to illustrate practices such as surveying and perspectival drawing, Demerliorem’s image relies on lines to demonstrate a specific technique. And rather than narrating a complete history of surveying and topography, Laussedat instead gives a selected account of the development of similar practices over time. In his chapter from Recherches devoted to the Renaissance, he paid special attention to the graphometer, a device attributed to the mathematician, engraver, and calligrapher Philippe Danfrie (1531-1606) for taking horizontal and vertical angle measurements. Danfrie even devoted an entire treatise to the topic, the Declaration de l’usage du graphometre (1597), which included a series of engravings that echoed Demerliorem’s [15]

![]() |

| Engravings demonstrating Danfrie’s surveying methods as applied to buildings, from Laussedat, Recherches sur les instruments, les méthodes et le dessin topographiques, 76-77. |

In the first, a surveyor is shown using a graphometer to measure the height of a tower. In the second, the object of measurement is a building sitting atop a mountain. In both examples, the method is almost exactly the same. The surveyor uses a graphometer to determine the angle between lines connecting the graphometer to the base and the top of the tower. Danfrie illustrates the constructed angles using dark, engraved, and hatched lines traveling through space. Other engravings show the same process, this time applied to measuring the width of various fortifications. Whereas one shows three different surveyors using graphometers to measure the distance to a building using triangulated point, another features two men using multiple lines to measure the dimensions of a fortified town. And finally, in an image from the final pages of Danfrie’s treatise—as if anticipating Laussedat’s own métier—surveyors are measuring a building’s façade and side elevation. It is an image of architecture ensnared in a tangle of projecting, rectilinear lines.

Here, Demerliorem’s and Danfrie’s engravings become significant for another set of reasons. First, Laussedat includes several of these and similar images in the first volume of his Recherches as didactic examples illustrating the importance of constructed lines to topographic measurement. These lines may be abstract and conceptual, and are in some sense symbolic of the process they represent. Yet for the purposes of practices like geodesy and photogrammetry, such lines are functional and real. They demonstrate, as Claudia Brodsky tells us in her study of Réne Descartes’ architectonics, how a “line is itself a thing in the world because it is not an imitation of a thing.”[16] In other words, the lines emanating from graphometers and trigonometers in Demerliorem’s and Danfrie’s engravings are far more than constructions: they are lines traveling through the air. The fact that this is the case may seem like a truism, but it is important to recall that one of the foundational principles of perspectival drawing is that such lines have to actually emanate from an object and travel through the air into the painters eye. Leonardo da Vinci, for example, theorized that such lines travel “in a direct line from its cause to its object or the place at which it strikes” only through “air of uniform density.”[17] And later, Albrecht Dürer would distinguish between reflected and “refracted lines of sight, as the thing is seen through two different media, such as air and water, air and glass, or other different transparent substances.”[18]

These distinctions between reflection and refraction, or between mirrors and lenses and their role in the construction of perspectival views suggest an aerodynamical purpose for the photogrammetric line. If rules of perspectival construction assume that the air though which lines travel is of a uniform density, then the use of lenses would, in effect, interrupt the direction of the line. A line that travels through the air and enters through a lens is therefore subjected to a kind of air resistance. Diagrams showing the entry of light rays into an eye or camera show lines bending as they move through a lens—a convention that no doubt recalls the way aerodynamic or hydrodynamic solids (such as Marey’s fish-shaped “pisciforme” objects) interrupt the flow of fluids. Yet what is the product of this air resistance?

From Camera Lucida to Panorama

As the photogrammetric line moved through the air and encountered resistance, Laussedat developed a series of technological interventions and surveying techniques that capitalized on this force. Such devices were aerodynamic by virtue of the fact that they used mirrors and lenses to, in a sense, interrupt to direction of flow of photogrammetric lines. Yet in investigating this trajectory even farther, the origins of the photogrammetric line in light of Laussedat’s earlier work in surveying, geodesy, and topography are worth examining in closer detail.

Laussedat’s photogrammetric work must here be understood as part of a larger tradition of practices dealing with geometric constructions and optics. An important touchstone is the Swiss mathematician Johann Heinrich Lambert (1728-1777), who wrote several important treatises outlining a geometrical understanding of perspective. In 1752, he published Anflage zur Perspektive, a text that distinguished between tactile and visual perceptions of the world and that would preface his most well-known book on optics, the Photometria from 1760. In that book, Lambert offered his own explanations on the nature of light while rejecting previous work regarding corpuscular and wave theories.[19] Yet a year earlier, he had already applied this line of investigation to his first work on geometric construction in La perspective affranchie de l’embaras du plan géometral (1759). Lambert followed the same reasoning here from centuries before, indicating that lines travel from objects to the eye. In principle, he agreed with the notion that such lines traveled in the air without interruption, yet his wording also admitted to an aerodynamic understanding: he observed that objects were “insensitive” to any effects caused by the “superfluous” air.[20] Put another way, there was no real difference between pure perspectival constructions and those, like aerial perspective, which took the effects of atmospheric phenomena into account.[21]

This was an important observation for the early chroniclers of photogrammetry like the American surveyor and naval engineer John Adolphus Flemer, who noted in his study from 1906 that Lambert was the first to lay down rules for monocular optics as well as “for finding the point of view of a perspective and to determine the dimensions of objects represented in perspective.”[22] Flemer’s book is an important vantage point through which developments in photogrammetric methods can be understood. He wrote it while consulting people like the German architect Albrecht Meydenbauer (1834-1921) and the Canadian surveyor Édouard Deville (1849-1924), two figures that would inherit, expand, and popularize Laussedat’s own work.

Appearing inside Flemer’s comprehensive text is an important link connecting earlier treatises on geometry to more contemporary work on photogrammetry and geodesy. He notes that Lambert’s theories were generally unknown until 1791, when the hydrographer and cartographer Charles-François Beautemps-Beaupré (1766-1854) created a set of maps and elevations of the coast of Van Diemansland (Tasmania) and the islands of the Santa Cruz Archipelago (also known as the Queen Charlotte Islands) in the South Pacific Ocean.[23] An account of the techniques first appeared in an appendix to Rear Admiral Bruny-D’Entrecasteaux’s 1808 account of the very same voyage—a meticulously planned expedition to the South Pacific to search for the remains of Jean-François de Galaup (the Comte de Lapérouse), who disappeared mysteriously in 1788.[24] Beautemps-Beaupré’s drawings would become the focus of a separate text, the Méthode pour la levée et la construction des cartes et plans hydrographiques (1811). Some of the most important images from this text anticipate the published aerostatic maps of aeronauts like Tissandier, Jules Dupuis-Delcourt, and James Glaisher. Like these maps, which combine cartographic images and ascension diagrams in order to describe a balloon's transit over a city, Beautemps-Beaupré's engravings combine plan and elevation into a single document, here describing the views of the Santa Cruz group while at the same time providing a topographic reference.

![]() |

| Engraving showing topographical derivation of Santa Cruz Islands from a drawn elevation, from Charles-François Beautemps-Beaupré, Méthodes pour la levée et la construction des cartes et plans hydrographiques, publiées en 1808 (Paris: Imprimerie Impériale, 1811), n.p. |

More importantly, Beautemps-Beaupré fashioned his maps from the drawn elevations. The construction lines needed for this process were inferred. Due to problems with compass readings, he calculated and drew the images using angle measurements derived from graphometers and Borda circles.[25]

Contemporaries celebrated Beautemps-Beaupré’s maps and elevations of the Santa Cruz group as the pinnacle of marine surveying techniques, and yet the importance of these images extended well beyond hydrographic and naval circles. One to take notice of such applications was the astronomer and physician François Arago (1786-1853). In July 1839, Arago submitted a report to the Chambre des Députes introducing Louis Daguerre’s and Joseph Nicéphore Niépce’s discovery of the daguerreotype process. His famous report celebrated the new medium’s aesthetic possibilities while imagining how current scientific practices could have advanced if such a technology would have appeared earlier. For example, Arago imagined the benefits of daguerreotypes to Napoléon Bonaparte’s 1798 survey of Egypt, noting how the technique could be used to capture images of hieroglyphs as well as “to trace the exact dimensions of the highest walls, the most inaccessible buildings.”[26] It is a statement that is as fanciful as it is prescient, and though it forecasts a possible application for the daguerreotype process, it is about as clear a statement regarding the use of photographic images for measuring buildings as could exist at the time.

Laussedat also understood the importance of Beautemps-Beaupré’s maps of the Santa Cruz group. In one of his earliest articles concerning the application of photogrammetric techniques to surveying, he included reproductions of Beautemps-Beaupré’s maps as well as extensive passages from the Méthode pour la levée et la construction des cartes et plans hydrographiques, citing both as “very fruitful and laborious” for geography.[27] Here, Laussedat acknowledged the influence of his mentor, Capitaine Le Blanc of the Corps de Génie, who was the first to apply Beautemps-Beaupré’s method of deriving plans from drawn elevations to military surveying. These methods were fraught with error, not because of the instruments, but rather because of the fact that the drawn elevations were, in Laussedat’s words, “imperfect and incomplete.”[28]

The solution to these problems would rely on a novel application of an existing technique. In 1849, the architect Auguste Bourgeois, who would become famous for the restoration of Philibert de l’Orme’s Château d’Anet in Dreux, introduced Laussedat to the use of a camera lucida (“chambre claire”) for drawing “bas-reliefs, round bumps, and monuments.”[29] The camera lucida is a device using a small four-sided sighting mirror to superimpose an image of a drawing surface, allowing an artist to literally view an object while drawing it. As described in 1807 by its credited inventor, the English physicist William Hyde Wollaston, one of the advantages of the camera lucida would be to allow an artist “in acquiring at least a correct outline of any subject.”[30] As if following Wollaston’s own directions for using the device, Laussedat and Bourgeois used a camera lucida to draw the southern façade of the Hôtel des Invalides in 1850.

![]() |

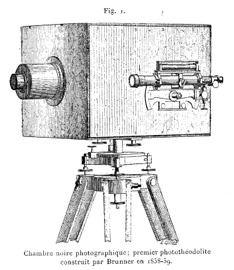

| Laussedat’s explanation of how camera lucida was used to draw the dome at Les Invalides, from Laussedat, “Les applications de la perspective au lever des plans: vues dessinées a la chambre claire—photographies,” Annales du Conservatoire des arts et métiers, publiées par les professeurs, Vol. 3,, No. 2 (1891), 316. |

They correlated the images with measurements taken using a plane table and a compass. And as if echoing his own pronouncements from 1839, Arago suggested to Laussedat that he meet Paul-Gustave Froment, who would be able to turn the camera lucida into a kind of measurement device.[31] Froment, famous for helping design and construct Léon Foucault’s pendulum, created a version of the device that converted the camera lucida into a telescope modeled on Galileo’s. Laussedat wrote in an 1854 issue of the Mémorial de l'officier du genie that the new camera lucida, mounted on adjustable supports and sporting a spirit level, was now poised to help take more accurate measurements.[32] He used this device to create two of the most famous images in the history of photogrammetry: constructed views of the forts at Mont-Valérien and Vincennes.

![]()

![]() |

| Diagrams showing derivation of plans from elevation drawings of Vincennes (top) and Mont Valerien (bottom), from Laussedat, Recherches sur les instruments, les méthodes et le dessin topographiques, n.p. |

These measured drawings demonstrated how to derive a plan from an elevation through a complicated tangle of straight lines and control points. These images do not feature the same kind of spatial complexity as Danfrie’s engravings of a graphometer in use. No lines are traveling through the air. Yet any lack of spatial imagination is more than made up by the fact that this is the very image of accuracy. In other words, these measurements and drawings relied on lines that, unlike Bosse’s threads, suddenly dematerialized in face of geometric complexity.

Though Laussedat’s version of the camera lucida did have important architectural origins, it was by no means the only one to be marshaled for architectural purposes. By the 1820’s, for example, Léon Vaudoyer described the using of a camera lucida for sketching purposes as mere “fashion,” instead claiming its importance to architectural drawing.[33] Laussedat also had an eye for the history of such devices—and his place in that history. In 1868, he hosted Viollet-le-Duc and the architect Henri Revoil, who was gaining notoriety as the inventor of a telescope-like camera lucida called the téléiconographe at the École Polytechnique. Viollet-le-Duc’s interest in such a device is well documented. He not only used one for his studies of Mont Blanc,[34] but also claimed that the téléiconographe would allow the architect to become a “true draftsman” by observing nature.[35] Laussedat probably invited Viollet after reading his 1868 article introducing the device in the Gazette des architectes et du bâtiment called “Le téléiconographe.”

![]() |

|

![]() |

| Viollet-le-Duc, “Le téléiconographe,” Gazette des architectes et du bâtiment. Revue bi-mensuelle publiée sous la direction de MM. E. Viollet-le-Duc fils et A. de Baudot, architecte, Vol. 6, No. 20 (1868-1869). Collection, Drawing with Optical Instruments—Devices and Concepts of Visuality and Representation Collection, Max Planck Institute for the Historyof Science. |

Viollet’s piece featured Revoil’s drawings of details from the château at Pierrefonds as examples of how designers could use the device for “obtaining accurate reproductions.”[36] Laussedat could not disagree more, recalling in later articles that during Viollet’s visit to the École Polytechnique, he tried to convince the two architects that he was in fact was the inventor of the device and pointed to an article from an 1854 issue of the Mémorial de l'officier du genie as proof.[37] Furthermore, Laussedat believed that the very thing that distinguished his device was that unlike Revoil’s, which was used only for “magnifying images,” his was an instrument for “measuring distances.” To help differentiate his version of the camera lucida from Revoil’s “fake,” he gave it a new name: télémetrographe.[38]

In subsequent essays and conferences, Laussedat referred to the method of applying the camera lucida as iconométrie, or the art of “drawing pictures, well-drawn images, and the actual sizes of objects represented therein.”[39] Télémetrographie, on the other hand, was a “new art” of measuring distances using camera lucidas that would be deployed for important architectural purposes. It had its origins in aerial projection. In 1851, not long after Laussedat developed his telescope-like camera lucida, he attempted to take one in the air aboard a balloon to make measured drawings of the cliffs along the English Channel. He derived his method from a passage from of Gaspard Monge’s Géometrie descriptive (1798 et seq.) describing how a single drawing could yield multiple perspectives and, more importantly, multiple plans.[40] Noting that Monge’s method of perspectival construction could be applied to images on a vertical plan, Laussedat saw no reason why it could not be used with images on a horizontal plan. In his words, “in the case in question, the object or objects are supposedly contained in the same horizontal plan, so by tracing rays through the visual vertical perspective and seeking their mark on a horizontal array, we obtain a figure similar to the natural contour, that is to say, a plan whose scale will generally be easily determined by a measure taken in the field.”[41] In other words, a vertical perspective could be obtained from a horizontal perspective.[42] The skeleton key to this process was the horizon line, which would allow a vertical plane to be deduced from a horizontal plane via a series of translations borrowed from descriptive geometry. Laussedat included an engraving showing the results of this process—the contour of a river presented as a having been derived from an oblique aerial drawing.

![]() |

| Laussedat’s illustration of riverbank drawn via balloon, from Laussedat, “Les applications au lever des plans. Vues dessinées a la chambre claire—photographies,” Annales du Conservatoire des arts et métiers, publiées par les professeurs, Vol. 2, No. 2 (1890), 316. |

And as if to reinstate the lack of difference between a vertical and horizontal perspective, the process could be applied to drawing from buildings. For Laussedat, “In a flat country where we sometimes meet with buildings of great height, a single panorama taken from the top of one of these buildings, which would contain roads, canals, rivers and other accidents remarkable the surrounding terrain, even buildings that are discovered on foot, would be sufficient to provide the basis of a partial recognition that could be still fairly accurate (within a limited radius, however), if the soil was substantially level.”[43]

Laussedat’s invocation of panoramic views suggests another architectural application for his methods, one borne out of the political realities of the time. Soon after the beginning of the Franco-Prussian War on 19 July 1870, advancing Prussian troops cut the vital telegraph lines across the Seine. Laussedat was appointed as the head of a group whose primary task was to reestablish communications between a besieged Paris and the world. Acting along with luminaries such as the mathematician Jules Antoine Lissajous, the Commission de Telegraphie Optique tried using a heliograph—a device using mirrors to reflect bursts of sunlight corresponding to telegraphic messages—for communicating with positions outside Paris.[44] Laussedat was likely familiar with an early version of the heliograph invented by the German mathematician Karl Friedrich Gauss in 1810 as a means to use sunlight and mirrors to take geodetic readings. Yet it was not until 1869 that Henry C. Mance, a British officer with the Persian Gulf Telegraph Department, invented the first true heliograph while stationed in India and Afghanistan. Mance’s device consisted of a small-diameter mirror placed atop a flexible tripod. It would be the one favored by Laussedat and Lissajous during the Siege of Paris for its ability to transmit Morse code messages to forces up to 30 miles away.[45] In this sense, if the télémetrographe can be thought of a device that connects the eye to an object through a line that corresponds to the device’s focal length, this would mean that the heliograph converted the focal length to something that was more readable, tangible, and that could be marshaled for important purposes. In other words, the heliograph came closer to making the line connecting the air between viewer and subject into a kind of measured reality, or as the philosopher François Dagognet would put it, “Letters and words were transformed into trails of fire!”[46]

![]()

![]() |

| (Top) Poyet’s engraving of Laussedat’s télémetrographe, from Laussedat, “Les reconnaissances a grandes distances: le télémetrographe,” La nature No. 629 (20 June 1885), 40. (Bottom) Prussian troops, as seen through a télémetrographe, from Laussedat, Recherches sur les instruments, les méthodes, et le dessin topographiques, 118. |

Yet it was a reality that had to be bounded before it could be used properly. When discussing his work during the Siege of Paris, Laussedat introduced a provocative image showing a group of Prussian soldiers digging a trench in front of a wall. The image appears as if viewed through a télémetrographe—the view is bisected by a horizontal line that is itself divided into notches corresponding to increments of minutes. Published in an 1885 issue of La nature, the image demonstrates an essential point: that under the most ideal conditions, the image itself is bounded by a 25º viewing angle.[47] Using similar images drawn by Prussian troops through a field telescope, Laussedat referred to this kind of drawing as a “projected image,” a term suggesting how the télémetrographe creates an image bounded and contained by the projection screen.[48] Furthermore, the breaking down of the image into degrees calls attention to the télémetrographe’s swiveling motion, an indication that the resultant “projected image” was a kind of panoramic image. It is an apposite implication because Laussedat claimed that one of the most famous panoramic images of the time, Henri Félix Emmanuel and Paul Philippoteaux’s dramatic Bombardement du fort d’Issy (1871), was a product of télémetrographie.[49] Philippoteaux fils wrote in an 1882 issue of the New York Times how the panoramic image elided any momentary distinction between nature and artifice: “A spectator comes in, who never saw a panorama before, and, puzzled to know how far the canvas is from him, he takes a copper out of his pocket and shies it at the picture. It is too small to do any great harm, for after striking the canvas it of course falls to the floor; still, it is a satisfaction for the man who is so lavish, since he practically demonstrates to himself where the panorama has an actual beginning and where it really ends.”[50] The effect on the viewer was literally calculated. Placed inside a building erected temporarily near the Champs-Élysées, the Philippoteaux’s panorama used exaggerated perspectives to trick an individual observer’s sense of depth perception.

The panorama was therefore an optical illusion requiring a specific kind of architectural intervention. This was the point made by the artist Germain Bapst in his report of panoramas prepared for the 1889 Exposition Universelle, or World's Fair in Paris. Bapst believed that the panorama functioned only to the extent that a viewer could not distinguish between the surface of the panorama wall and the distance depicted therein. In other words, “while the observer sees only a work of art, he believes to be in the presence of nature.”[51] And in order to fool the senses in such a profound way, architecture had to be deployed in a very specific way, even down to the measurements.[52] Bapst also included an image from the Le génie civil showing builders erecting the iron framing for a panorama (Fig. 4.33).

![]() |

| Iron structure for panorama, from Germain Bapst, Essai sur l’histoire des panoramas et des dioramas (Paris: Masson, 1891), 9. |

And though this image suggests that the panorama was necessarily architectural, like Laussedat, Bapst declared that the most important part of the illusion was the horizon line. As a convention that brought panoramic painting in line with rules of perspectival construction, here, the horizon line was not necessarily physically inscribed on the inside of the building, but was nevertheless present.[53] The horizon line, as art and film historian Alison Griffiths has remarked, was the very thing that made the optical illusion seem more real.[54]

It is in this sense that the horizon line is like the photogrammetric line. Both share a quality in that though they are not explicitly visible, they are implicitly perceived. Both are also necessary for the construction of images. Unlike the horizon line, the photogrammetric line does not seem to be bounded by architecture. This, however, would change as a series of parallel developments had the effect of containing the photogrammetric line inside an architectural object.

One key to understanding this development is an 1886 article in Scientific American dedicated to the Philippoteauxs’ cyclorama painting depicting the Battle of Gettysburg. Titled “The Cyclorama,” the article describes in depth how the two artists created the giant painting in 1884, which measured 22 feet in height and 89 feet in diameter. As if undermining Laussedat’s description of the Philippoteauxs’ painting process, the reporter explained how the artists used cameras to capture the landscape and transferred the images to the canvas.

![]() |

| mage describing the Philippoteaux’s surveying method in preparation for painting the Gettysburg cyclorama, from “The Cyclorama,” Scientific American (6 November 1885), 296. |

The Philippoteauxs’ achieved this “artistic transcript of photographic views of the field” by placing a dry-plate camera atop a platform of the same height as the one to be mounted inside the cyclorama.[55] Around this, and marked according to a 40-foot radius, they drove stakes into the ground corresponding to the vertical spars that would provide the painting’s structure. They captured images of the background, middle, and foreground, all combined together into ten views of the landscape, with a grid superimposed over each. This grid became a reference for transferring the images onto the large canvas. In the reporter’s words, “This blending of the ten views and the aerial perspective was a question of artistic achievement. The outlines were determined, to a great extent, mechanically.”[56]

It was a poignant description. The Philippoteauxs’ reliance on grids and cameras recall another series of developments that would instrumentalize and (literally) mechanize Laussedat’s techniques. In 1886, Édouard-Gaston Deville (1849-1924), the Surveyor General of Canada, completed his photogrammetric surveys of the Canadian Rockies using Laussedat’s method of taking panoramic measurements from elevated places. He published detailed descriptions of his methods and results in the well-known Photographic Surveying, Including the Elements of Descriptive Geometry and Perspective (1895). Like Laussedat, Deville occupied himself with the problem of transferring a perspective view to a plan and devoted an entire section of his text to his experiments with perspectographs. Perfected and patented by the German architect Hermann Ritter in 1883, the perspectograph was an instrument by which a designer could translate a perspectival view to plan while having both on the same drawing surface.[57]

![]() |

| Ritter’s perspectograph, from Édouard-Gaston Daniel Deville, Photographic Surveying Including the Elements of Descriptive Geometry and Perspective (Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau, 1895), 76). |

The machine, though useful, was not well suited for surveying purposes because of its large size, and Deville had to devise a way to make the essential principles behind Ritter’s instrument more portable.[58] His solution would be to create his own device.

![]() |

| Method for applying Deville’s “perspectometer,” from Deville, Photographic Surveying Including the Elements of Descriptive Geometry and Perspective, 88. |

Like Alberti’s or Dürer’s variations on the painter’s veil, Deville’s “perspectometer” was a device that used a net or grid to interrupt the observer’s field vision in order to render an accurate perspective. Yet the perspectometer was different in two important ways. As Deville explained, the device was essentially a framed piece of transparent material on which a surveyor would draw a horizon line from which a perspectival grid emanated. It was a technique that was especially useful in capturing complicated terrains such as those found in the Canadian Rockies. When viewing such terrain, the grid would appear as a series of perspectival lines with a horizon line superimposed over the landscape beyond. Other images suggest something of a completely different order. Published in Deville’s treatise, and later in an 1893 article by Laussedat, these images of the Canadian Rockies show the perspectometer’s lines as a perspectival grid floating in the air and bisecting mountains.

![]()

![]() |

| (Top) “Canadian Grid Method” using perspectometer, from Deville, Photographic Surveying Including the Elements of Descriptive Geometry and Perspective, n.p. (Bottom) Completed method from Center for Photogrammetric Training, “History of Photogrammetry” (2008), 10. |

Deville’s perspectometer differed from Ritter’s perspectograph in another important way. Whereas Ritter’s device could be adjusted according to the kind of image used, Deville’s needed a degree of precision and uniformity. For this reason, he advocated that a perspectometer could yield accurate surveying results only when used in conjunction with a small dry-plate camera. To do this, and using the example of a camera he had invented for this purpose, Deville suggested that a surveyor first obtain triangulated points and use them to construct a large perspectometer grid on a large sheet of paper. Taking the camera’s focal length into consideration, it was then leveled and sighted through a transit telescope; a figurative line would therefore connect the vanishing point on the distant horizon line with the transit and camera lens. This process would not only calibrated the camera with geodetic control points, but in doing so, would also ensure that the camera was horizontally and vertically stable. Having used these, a surveyor would then take pictures of both the landscape and the perspectometer. The grid was then reduced and developed on a transparency plate. When soaked in a solution of mercury bicholride, the lines would then turn a ghostly white.[59] Deville then placed the white grid on the photograph, which could then be used as the basis for drawing a topographic map.

Deville’s critics pointed out that his method of “Perspective Surveying” amounted to excess labor. The same information could be yielded from plane table measurements in a shorter amount of time. To this, Deville claimed that the main advantage of his system, other than its portability, was that it allowed surveyors to ply their trade and save the difficult work of plotting for the office.[60] This was not to say, however, that the quality of work done outside in the open air would be distinguished from that done inside an office. The two, as it turned out, depended on each other. The lines constructed out on the field when using a single camera with a known focal length would then be instrumentalized in the office. This process depended not just on taking pictures, but also on photographing and developing the perspectometer itself. The perspectometer’s ghostly white lines therefore point to another important stage in the development of the aerial line. When manipulated, edited, and superimposed on a survey image, it is as if the grid tells of another story, one where the photogrammetric line has become a materialized abstraction thanks to the developing process.

The Photogrammetric Line, Enclosed

As the preceding examples demonstrate, the uses of camera lucidas and photographic cameras were not mutually exclusive. Deville, for example, believed that photographic cameras were better suited for fieldwork because of their relative portability. Laussedat would champion the photographic camera because it was a timesaving device. Portability and efficiency were especially important in the field of battle, and indeed the Franco-Prussian War became an important proving ground for surveying techniques. Laussedat’s interest in using the camera lucida in the field seems quaint when compared to how Prussian forces were already deploying photographic cameras during siege operations in Strasbourg and Paris.[61] And yet by the end of hostilities in 1871, there was evidence of a technology exchange of sorts between the former combatants.

The main channel for this exchange was Aimé Gerard’s 1864 article for Photographisches Archiv describing Laussedat’s methods to German readers.[62] This and subsequent articles in Journal des Débats and the Bulletin de la Société française de photographie caused great interest among military officers, many who applied the techniques described therein eagerly.[63] The most important reader of these articles was the German architect Albrecht Meydenbauer (1834-1921), who wrote a series of articles in 1865 explaining how such techniques could be applied equally to architectural and topographic plans. More importantly, in 1867, Meydenbauer traveled to the World's Fair in Paris to view Laussedat’s work.

It is not difficult to imagine that Meydenbauer would have been drawn to Laussedat’s work if only for the sole reason that in 1858, he attempted to draw a series of elevations using measured photographs he took of Wetzlar cathedral near Frankfurt.

![]() |

| (Bottom) Image of Wetzlar cathedral, with arrow indicating where Meydenbauer almost fell down while taking measurements, from Jörg Albert, “Albrecht Meydenbauer: Pioneer of Photogrammetric Documentation of the Cultural Heritage,” Proceedings of the 18th International Symposium CIPA 2001 Potsdam (Germany), September 18-21, 2001. (Top) Example of Meydenbauer’s Plane-Table method, from Rudolf Meyer, Albrecht Meydenbauer: Baukunst in historischen Fotografien (Leipzig: VEB Fotokinverlag, 1985). Library and Study Centre, Canadian Centre for Architecture. |

It was a process fraught with difficulties because the only cameras available for such tasks had wide-angle lenses that distorted the image and thus delayed the translation from photograph to architectural drawing. When he arrived in Paris, he saw the very instrument that would solve such problems: Laussedat’s Photothéodolite, an instrument combining the portability of a camera with the angle measurement capabilities of a theodolite.

![]() |

| (Top_ Three-way drawing of Laussedat’s “Chambre claire photothéodolite, from Laussedat, “Les applications de la perspective au lever des plans: vues dessinées à la chambre claire,” Annales du Conservatoire des arts et métiers, Vol. 3, No. 2 (1891), n.p. (Bottom) Engraving of Laussedat’s phototheodolite, from Laussedat, “Les Applications de la perspective au lever des plans: vues dessinées à la chambre claire—photographies,” Annales du Conservatoire des arts et métiers, Vol. 5, No. 2 (1893), 287. |

As the forerunner of the modern phototheolodite, Laussedat’s device consisted of a photographic camera with a 15-plate magazine and a detachable, side-mounted transit telescope. He began developing the instrument as early as 1851, shortly after the Committee on Fortifications purchased a photographic camera for surveying purposes.[64] And in 1852, he used the device alongside a compass and plane table to annotate and calibrate photographs with geodetic readings.[65] In 1854, the Académie des Sciences declared itself satisfied with Laussedat’s progress and allowed him to continue developing the techniques. Laussedat also had to wait for advancements in photographic development and settled on a collodion process. He described the device as one for “topographic reconnaissance” that could be applied to buildings as well.[66] By 1855, Nadar had begun to patent various techniques for taking aerial photographs from balloons. Like others, Laussedat took an interest in such techniques shortly after Nadar captured his first aerial photographs of the Place de l’Étoile from the balloon Géant in 1858.

![]() |

| Nadar’s image of Paris from aboard the Géant, 1858. |

Laussedat approached this new development with a tempered, methodical eye. As mentioned before, he saw aerial photography as a limited and inaccurate process, and even favored using kites if only because they allowed surveyors to control the height from which the photograph was taken by adjusting the length of the lanyard. In 1864, assisted by a Capitaine Javary, Laussedat took detailed, measured kite-photographs of the Paris fortifications and derived over 1500 geodetic control points from these images, an amount unheard of at the time.[67] The results of these trials were converted into a series of highly detailed maps that were exhibited at the 1867 Paris Exposition. They also brought a new term into existence, one that captured the architectural and urban connotations of this process: Métrophotographie.

Meydenbauer’s experience at the Exposition set off a small battle of attribution. Years later, a brief review of Laussedat’s innovations appeared in an issue of Sigmund Theodor Stein’s Das licht in dienste wissenschaftlicher Forschung claiming that Meydenbauer’s device provided superior imagery.[68] Another German publication also announced that Meydenbauer had already been exhibiting his techniques as early as 1865 at the Berlin Photographic Exposition.[69] Laussedat responded by claiming that his wood-framed phototheodolite was not only better constructed, but also better designed than Meydenbauer’s metal-framed device. Lighter, and more nimble, the French device was more attuned to the needs of photographic surveying.[70] Yet in looking at these criticisms, it is important to note the great care spent recognizing the lens manufacturer for each device. The German articles declared Busch’s Pantoskop lens as superior, and this must have come as a blow to Laussedat, who spilled a great amount of ink heralding the achievements of his Bertaud lens.

This relationship of the lens to the device merits special attention because it brings to light an important factor to consider in the development of the aerial line. The wood framing, designed by the “artist” Brunner, was paired with a Bertaud lens, which was touted as being completely free from aberration.[71] Laussedat described Brunner’s chassis not as a camera, but as a “chambre noire topographique.”[72] This unusual description is important because it distinguishes this device from the earlier camera lucida—Laussedat described the device not as a photographic camera, but rather as a “camera obscura.” Contemporary observers noted the historical significance of this variation in terminology. Thus in his history of photogrammetry, Flemer claimed that Laussedat’s design was “modeled after Niepce’s” but inspired by “della Porta.”[73] The Italian physicist Giambattista della Porta (1535-1615) is often cited as the inventor of the camera obscura. And though there existed, to a certain extent, variants of the camera obscura before della Porta’s time, Laussedat’s invocation of this well known device is important because it points to a complication in the histories of modernity and vision.

That the camera obscura is brimming with architectural metaphors is clear. In a darkened room with a hole in one wall, light enters from the outside and projects an image on the opposite wall. The camera obscura’s architectural enclosure performs some heavy lifting. On the one hand, it is a kind of medium whose resultant upside-down image distinguishes immediately between the act of seeing and the one who sees—in short, the projected image is an imitation of nature, yet is one that must be interpreted and turned to its proper orientation in order to be recognized as such. On the other hand, another distinction is evident, one in which the camera obscura appears as a technology that distinguishes modern from pre- and early modern vision.[74] Laussedat’s own camera obscura creates a problem for this distinction because by its very design and purpose, it collapses the distinction between perspectival construction and camera projection.[75]

With this collapse comes a momentary suspension of the camera obscura’s architectural implications. This is because the part of Laussedat’s phototheodolite that contributed to this collapse between photographic techniques and perspectival construction was not the wooden frame but rather the Bertaud aberration-free lens that was undoubtedly an important technical achievement. Yet Laussedat deployed it for the simple fact that it would allow the image produced inside the camera obscura to conform to the laws of perspectival construction, or as Bruno Latour would put it, to have the lines carve a “a regular avenue through space.”[76] For an 1891 conference dedicated to photogrammetry, Laussedat summarized the problem as one of rectifying a central projection vis-à-vis two parallel projections.[77] Citing Marey’s experiments in chronophotography and Jules Janssen’s recording of planetary transit as examples, he claimed that photogrammetry was part of a new field where photography excelled in making “the most delicate measurements.”[78] Yet it was Hippolyte-Mayer Heine who would put this principle in the most exacting terms when he defined “Métrophotographie” as a kind of perspectival construction where the distance from the eye to the image is equal to the focal length of the camera used.[79]

Whether in the field with a camera lucida, or in the office while developing images from a phototheodolite, photogrammetry was a practice wholly dependent on the creation and articulation of lines in the air. The photogrammetric line marks another stage in the development in the aerial line in that, as has been demonstrated, it relied on photographic development techniques to make them less conceptual and more material. Jonathan Crary compares the camera obscura to the Deleuzian assemblage, a device that is “simultaneously and inseparably a machinic assemblage and an assemblage of enunciation.”[80] The same could almost be said about Laussedat’s phototheodolite, except for the fact that it is not the camera obscura, but rather the photogrammetric lines that are “assemblages of enunciation.” Yet this is endemic to perspectival construction, some even arguing that perspective is itself a kind of cultural construction.[81] Others likened it to a machinic apparatus.[82]

![]() |

| Engraving from Réne Descartes, La dioptrique (1637). |

Like the lines entering the eye of Descartes’ La dioptrique or any other number of images demonstrating the principles on which a camera obscura receives and projects images, the photogrammetric line travels through the air and enters an architectural space of sorts. The camera obscura, however, is not wholly enclosed: as light must come in, so it must go out. In other words, it is a device that leaves an aperture exposed to the space outside. To be contained fully by architecture, the aerial line had to make another important series of transformations.

_______________________________

Notes

[1] Vittoria di Palma, “Zoom: Google Earth and Global Intimacy,” in Vittoria Di Palma, Diana Periton, and Marina Lathouri, eds. Intimate Metropolis: Urban Subjects in the Modern City (London: Routledge, 2009), 242.

[2] Hippolyte Meyer-Heine, La photographie en ballon et la téléphotographie (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1899), 4-5.

[3] Here, I use the term “photogrammetry” to describe the process and techniques of measuring buildings using photographs. This is deliberate and for the sake of clarity, especially since the term would be used decades later by the German architect Albrecht Meydenbauer. Even after Meydenbauer coined the term, Laussedat would still be referred to as the inventor of photogrammetry. The German surveyor and mathematician Guido Hauck (1845-1905) declared as much in “Neue Constructionen der Perspective und Photogrammetrie: Theorie der trinlinearen Verwandschaft ebener Systeme,” Journal für Reine und angewandte Mathematik, Vol. 1, No. 95 (1883), quoted in Laussedat, Notice sur les travaux scientifiques de M. Aimé Laussedat (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1884), 30.

[4] Expériences faites avec l’appareil a mesurer les bases appartenant a la commission de la carte d’Espagne, trans. Aimé Laussedat (Paris: Libraire Militaire, 1860); Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez, Frutos Saavedra Meneses, Fernando Monet, and Cesáreo Quiroga, Base centrale de la triangulation géodésique d’Espagne, trans. Aimé Laussedat (Madrid: Rivadeneyra, 1865); Tomás Soler and Mario Ruíz Morales, “Letters from Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero to Aimé Laussedat: New Sources for the History of Nineteenth Century Geodesy” Journal of Geodesy, No. 80 (2006), 313-321.

[5] Laussedat, Recherches sur les instruments: les méthodes et le dessin topographiques, Vol. 2 (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1898), 81: “[Q]uand le terrain est peu accidenté, on reconnaît immédiatement que l'image n'est autre chose que le plan de ce terrain à une échelle qui est donnée par le rapport de la distance focale de l'objectif à la hauteur de l'appareil au-dessus du sol.”

[6] A description of this image appears in Laussedat, “Recherches sur les instruments, les méthodes et le dessin topographiques: méthodes et instruments de dessin. Innovations principales proposées,” Annales du Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, publiées par les professeurs, Vol. 4, No. 3 (1902), 211-212: “Une vue de l'hôpital de Berck-sur-Mer (Pas-de-Calais), prise à 350m de hauteur avec un objectif dont la distance focale était de 0m, 206. Le point où la verticale du centre optique de cet objectif rencontre le plan de la photographie, c'est-à-dire, dans ce cas, le point de concours des perspectives de nombreuses verticales (arêtes des édifices), s'obtient immédiatement avec beaucoup de précision; il serait aisé, dès lors, connaissant, par exemple, la longueur du grand bâtiment qui est de 121m, 80, de vérifier la hauteur indiquée par M. Wenz, de déterminer l'inclinaison de l'axe optique, puis de construire, à une échelle choisie, le plan de tous les bâtiments représentes, le bord mouillé du rivage au moment de l'opération, enfin de trouver la hauteur des principaux édifices.”

[7] Michel Foucault makes a similar observation about lines of sight in his study of Velazquez’ Las Meninas: “From the eyes of the painter to what he is observing there runs a compelling line that we, the onlookers, have no power of evading: it runs through the real picture and emerges from its surface to join the place from which the real picture emerges from its surface to join the place from which we see the painter observing us; this dotted line reaches out to us ineluctably, and links us to the representation of the picture.” Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (New York: Vintage, 1994 [1970]), 4.

[8] Anthony Grafton, Leon Battista Alberti: Master Builder of the Italian Renaissance (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), 124.

[9] Victoria Mitchell, “Drawing Threads from Site to Site,” Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture, Vol. 4, No. 3 (Fall, 2006), 348. See also Tim Ingold, Lines: A Brief History (London: Taylor & Francis, 2007), 159.

[10] Here I am borrowing terminology from Martha Macintyre and Maureen Mackenzie, “Focal Length as an Analogue of Cultural Distance,” in Elizabeth Edwards, ed., Anthropology and Photography 1860-1920 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 158-164.

[11] Mitchell, “Drawing Threads from Site to Site,” 348.

[12] Marco Vitruvius Pollo, Ten Books on Architecture, trans. Ingrid Rowland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 103-4.

[13] Laussedat, Recherches sur les instruments, les méthodes et le dessin topographiques, Vol. 1, 19: "C'est à peine si l'on trouve à mentionner, d'après Vitruve, un niveau d'eau à simple cuvette creusée dans une règle assez longue posée sur le sol, qui pouvait aussi fonctionner à l'aide de perpendicules, désigné sous le nom de chorobate […] dont l'usage ne devait pas être, à beaucoup près, aussi commode que celui de la dioptre horizontale et de la mire à voyant.”

[14] Vitruvius, Ten Books on Architecture, 104.

[15] Danfrie is credited with inventing the term “graphometer.” The fact that it was a device with wide applications is evident from the title of his treatise, Declaration de l'usage du graphometre: par la pratique duquel l'on peut mesurer toutes distances des choses de remarque qui se pourront voir et discerner du lieu ou il sera posé: et pour arpenter terres, bois, prez, & faire plans de villes et forteresses, cartes geographiques, & generalement toutes mesures visibles: et ce sans reigle d'arithmetique (Paris: Danfrie & Carmes, 1597). The military engineer Benedit de Vassalieu dit Nicolay used Danfrie’s graphometer to create his own bird’s-eye views and maps of Paris in 1609. Hilary Ballon, The Paris of Henry IV: Architecture and Urbanism (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991), 220-233.

[16] Claudia Brodsky Lacour, Lines of Thought: Discourse, Architectonics, and the Origins of Modern Philosophy (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996), 144.

[17] Leonardo da Vinci, The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, ed. and trans. E. MacCardy (London: Jonathan Cape, 1938), 343, 345-346, 352-353, quoted in Carol M. Richardson, Kim Woods, and Michael W. Franklin, eds., Renaissance Art Rediscovered: An Anthology of Primary Sources (Malden, Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007), 52.

[18] Albrecht Dürer, “A Fragment on Painting,” in William Martin Conway, ed. The Literary Remains of Albrecht Dürer (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1889), 175.

[19] J.J. Gray and Laura Tilling, “Johann Heinrich Lambert, Mathematician and Scientist, 1728-1777,” Historia Mathematica, Vol. 5, Issue 1 (Feb., 1978), 21.

[20] Johann Heinrich Lambert, La perspective affranchie de l’embaras du plan géometral (Zurich: Heideggeur, 1759), 5: “La seconde Experience, dont nous servirons, est, que les raïons de la lumière émanent en lignes droites de chaque point des Objets, & que par conséquent leur image paroit toujours sur la ligne, qu'on en tire dans l'oeuil. Il est évident, qu'on neglige ici la réfraction, parce que celle que la lumière soufre dans l'air est for petite, & pour la plus part des Objets, que l'on veut mettre en perspective, elle est tout à fait insensible, desort qu'il seroit superflu, d'y avoir égard.”

[21] Renzo Dubbini, Geography of the Gaze: Urban and Rural Vision in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 94.

[22] John Adolphus Flemer, An Elementary Treatise on Phototopographic Methods and Instruments, Including a Concise Review of Exectued Phototopographic Surveys and Publications on This Subject (New York: Wiley & Sons, 1906), 5, 35.

[23] Ibid., 5.

[24] Antoine Raymond Joseph de Bruni D’Entrecasteaux and Élisabeth Paul Edouard de Rossel, Voyage de Dentrecasteaux, envoyé a la recherche de La Perouse (Paris: Impremerie Imperiale, 1808), n.p. Edouard Collin provided the engravings that illustrated Beautemps-Beaupré’s maps and techniques. A year earlier, Beautemps-Beaupré published Atlas du voyage de Bruny-Dentrecasteaux contre-amiral de France, commandant les frégates la recherche et l’esperance fait par ordre du gouvernement en 1791, 1792 et 1793 (Paris: Impremerie Imperiale, 1807). Earlier accounts of Lapérouse’s expedition appear in Louis-Marie-Antoine Destouff de Milet-Mureau, ed., Voyage de La Pérouse autour le monde, publié conformément au décret du 22 avril 1791 (Paris: Plassan, 1798) and Jacques Julien Houton de la Billardérie, Relation du voyage a la recherche de La Pérouse, fait par le ordre de l’assemblée constituante (Paris: Jansen, 1799).

[25] D’Entrecasteaux and de Rossel Voyage de Dentrecasteaux, 600; Matthew Flinders, A Voyage to Terra Australis, Undertaken for the Purpose of Completing the Discovery of that Vast Country, and Prosecuted in the Years 1801, 1802 and 1803 (London: G.W. Nicol, 1814), 525. For more on the Borda circle, see Ken Alder, The Measure of All Things: The Seven-Year Odyssey and Hidden Error that Transformed the World (New York: Free Press, 2003).

[26] François Arago, Rapport de M. Arago sur le daguerréotype, lu à la séance de la Chambre des députes le 3 juillet 1839 et à l’Académie des sciences, séance du 19 aôut (Paris: Bachelier, 1839), 30-31: “Munissez l’institut d’Egypte de deux ou trois appareils de M. Daguerre, et sur plusieurs des grandes plances de l’ouvrage célèbre, fruit de notre immortelle expédition, de vastes étendues d’hiéroglyphes réels iront remplacer des hiéroglyphes fictif ou de pure convention; et les dessins surpasseront partout en fidélité, en coleur locale, les oeuvres des plus habiles peintres; et les images photographiques étant soumises dans leur formation aux règles de la géométrie, permettront, à l’aide d’un petit nombre de données, de remonter aux dimensions exactes des parties plus élevées, les plus inaccessibles des édifices.” Flemer interprets this as being an indication that Arago was familiar with Beautemps-Beaupré’s technique. Flemer, “The Progress of the Phototopographic Surveying Method,” The International Journal of Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin and American Process-Book, Vol. 12 (New York: E. & H.T. Anthony, 1900), 158.

[27] Laussedat, “Les applications de la perspective au lever des plans: vues dessineés à la chambre claire [1er article],” Annales du conservatoire des arts et métiers, publiées par les professeurs, Vol. 2, No.2 (1890), 294.

[28] Ibid., 297.

[29] Ibid., 297, n.1.

[30] William Hyde Wollaston, “Description of the Camera Lucida,” in Alexander Tilloch, ed., The Philosophical Magazine, Vol. 27 (Feb.-May, 1807), 346.

[31] Laussedat, “Les applications de la perspective au lever des plans: vues dessineés à la chambre claire [1er article],” 298, n.1.

[32] Laussedat, “Mémoire sur l’emploi de la chambre claire dans les reconnaissances topographiques,” Mémorial de l’officier du génie, ou recueil de Mémoires, expériences, observations et procédés généraux propres à perfectionner la fortification et les constructions militaires, No. 16 (Paris: Mallet-Bachelier, 1854), 221; Recherches sur les instruments, les méthodes et le dessin topographiques, 187-188.

[33] Léon Vaudoyer to Antoine-Laurent-Thomas Vaudoyer, 4 April 1827, in David Van Zanten, Designing Paris (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1987), 253, n.19: “[N]otre maniere de travailler, aujourd’hui, n’est pas un mode; elle est positive et incontestablement supérieur à celle de nos prédecesseurs.” In his study of Vaudoyer, Barry Bergdoll notes how Vaudoyer believed that the camera lucida “was an instrument useless in the hand of any but the most gifted draftsman. For the architect it was a tool that would help promote drawing from a mere form of recording to an instrument of positive knowledge, almost of objective ‘scientific’ inquiry. The implication was that the aim of drawing was no longer to discern some abstract truth, some ideal, but rather to be the medium for probing the positive knowledge of architrecture embodied in the material artifact itself.” Barry Bergdoll, Léon Vaudoyer: Historicism in the Age of Industry (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994), 77.

[34] A striking example of this technique appears in Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, Le massif du Mont Blanc: étude sur sa constitution géodésique et géologique sur ses transformations et sur l'état ancien et moderne de ses glaciers (Paris: Baudry, 1876), 7.

[35] Viollet-le-Duc, Débats et polémiques à propos de l’enseignement des arts du dessin, Louis Villet, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (Paris: Ecole nationale superiure des beaux-arts, 1984), 100, quoted in Paula Young Lee, “’The Rational Point of View’: Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc and the Camera Lucida,” in Jan Birksted, ed., Landscapes of Memory and Experience (London: Spon Press, 2000), 75, n. 21: “La véritable dessinateur n’est pas un photographe reproduisant un modèle posant devant lui, mais un observateur étudiant ce modèle, de façon à en connaître si bien la forme, la raison d’être, de se mouvoir, les diverses apparences suivant les circonstances extérieurs.”

[36] Viollet-le-Duc, “Le téléiconographe,” Gazette des architectes et du bâtiment. Revue bi-mensuelle publiée sous la direction de MM. E. Viollet-le-Duc fils et A. de Baudot, architecte, Vol. 6, No. 20 (1868-1869), 203: “La chambre claire n'est (pour les personnes qui savent manier le crayon) qu'un moyen sûr et expéditif d'obtenir des reproductions exactes. Il n'en faut pas moins, même pour les dessinateurs, une certaine pratique, si l'on prétend utiliser le chambre claire; mais cette pratique n'est pas longue à aquérir.”

[37] Laussedat, Recherches sur les instruments, les méthodes et le dessin topographiques, 90, n.1: “M. Revoil était venu à mon observatoire de l'École Polytechnique avec son illustre confrère et ami Viollet-le-Duc. Je fis à ces messieurs l'accueil le plus courtois, tout en les prévenant de la nécessité où j'étais de les désillusionner. Je leur expliquai ce qui avait été fait depuis si longtemps et, après m'être assuré que M. Revoil n'avait pas songe à faire autre chose que des images amplifiees, je leur montrai le passage du Mémorial de l'Officier du Génie, année 1854, oú de trouve expose le principe de l'appareil destiné à mesurer les distances, et enfin la figure du Magasin pittoresque.”

[38] Ibid.: “Ce fut même ce qui me décida, à mon tour, usant de mon droit de paternité incontestable, en vertu des régles universellement adoptées de l'antériorité garantie par les publications imprimées, à appeler le mien du nom de télémetrographe qui indiquait clairement sa destination et avait en même temps l'avantage d'être un peu moins anguleux que celui de sa contrefaçon.”

[39] Laussedat, “L’Iconométrie et la métrophotographie, conférence du 28 février 1892,” Annales du conservatoire des arts et métiers, publiées par les professeurs, Vol. 2, No. 4 (1892), 374.

[40] Laussedat, “Les applications de la perspective au lever des plans: vues dessineés à la chambre claire [1er article],” 313, n.1. Laussedat identifies the passage as coming from Gaspard Monge, Géometrie descriptive, 4th ed., Barnabé Brisson, ed. (Paris: Courcier, 1820), 168: “Lorsqu'on a un tableau offrant la perspective d'un objet, prise d'un point déterminé, on peut en déduire le tracé d'une perspective du même objet prise du même point de vue, et sur un tableau différent. En effet, l'œil et le premier tableau étant déterminés de position, la direction des rayons visuels menés de l'œil à chacun des points de l'objet représenté se trouve fixée, et l'on peut en déduire par conséquent leur rencontre avec la surface d'un autre tableau dont la position est donnée.”

[41] Laussedat, “Les applications de la perspective au lever des plans: vues dessineés à la chambre claire [1er article],” 313: “Or, dans le cas dont il s'agit, l'objet ou les objets sont supposés contenus dans un même plan horizontal; en traçant donc les rayons visuels au moyen de la perspective verticale et en cherchant leurs traces sur un tableau horizontal, on obtiendra une figure semblable au contour naturel, c'est-à-dire un plan dont l'échelle sera généralement facile à déterminer par une mesure prise sur le terrain.”

[42] Ibid.: “Cherchons à effectuer, le plus simplement possible, cette transformation d'une perspective verticale en une perspective horizontale.”

[43] Ibid., 317: “Dans les pays de plaine où l'on rencontre quelquefois des édifices d'une grande hauteur, un seul panorama pris du sommet de l'un de ces édifices et qui contiendrait les routes, les canaux, les cours d'eau et les autres accidents remarquables du terrain environnant, même des édifices dont on découvrirait le pied, suffirait pour fournir les éléments d'une reconnaissance partielle qui pourrait être encore passablement exacte (dans un rayon limité toutefois), si le sol était sensiblement de niveau.”

[44] Maurice Crosland, “Science and the Franco-Prussian War,” Social Studies of Science, Vol. 6, No. 2 (May, 1976), 203.

[45] William Rattle Plum, The Military Telegraph During the Civil War in the United States, with an Exposition of Ancient and Modern Means of Communication, and of the Federal and Confederate Cipher Systems, Vol. 1 (Chicago: Jansen, McClurg & Co, 1882), 30.

[46] François Dagognet, Étienne-Jules Marey: A Passion for the Trace, Robert Galeta and Jeanine Herman, trans. (New York: Zone Books, 1992), 42. In his famous discussion of Velazquez’ Las Meninas, Foucault makes a similar connection between the transmission of light, communication, and lines: “And as it passes through the room from right to left, this vast flood of golden light carries both the spectator towards the painter and the model towards the canvas; it is this light too, which, washing over the painter, makes him visible to the spectator and turns into golden lines, in the model's eyes, the frame of that enigmatic canvas on which his image, one transported there, is to be imprisoned.” Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences, 5-6.

[47] Laussedat, “Les reconnaissances a grandes distances,” in La nature: Revue des sciences et de leurs applications aux arts et à l'industrie, No. 629 (20 June 1885), 40: “En général, dans les lunettes terrestres, le produit du champ par le grossissement est sensiblement constant et de 25º environ.”

[48] Ibid., 41.

[49] Laussedat, Recherches sur les instruments, les méthodes et le dessin topographiques, 117, n. 1: “Le télémetrographe donne, en effet, des panoramas cylindriques, et c'est vraisemblablement sa participation à nos travaux de reconnaissance qui a suggéré au peintre Philippoteaux l'idée de son célébre Bombardement du fort d' Issy; mais les éléments de ces panoramas peuvent être considérés comme plans à cause de la grandeur de rayon, comparée a l'étendue d'un champ ou même du plusieurs champs de lunette juxtaposes.”

[50] “The Panorama of a Battle,” The New York Times, September 17, 1882.

[51] Germain Bapst, Essai sur l’histoire des panoramas et des dioramas, extrait des rapports du jury de l’exposition universelle de 1889 (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1889), 8: “Le panorama est une peinture circulaire exposée de façon que l'oeil du spectateur, placé au centre et embrassant tout son horizon, ne rencontre que le tableau qui l'enveloppe. La vue ne permet à l'homme de juger des grandeurs et des distances que par la comparaison; si elle lui manque, il porte un jugement faux sur ce que sa vue perçoit … Lorsqu'on voit un tableau, quelque grand qu'il soit, renfermé dans un cadre, le cadre et ce qui entoure le tableau sont des points de repère qui avertissement que l'on n'est pas en présence de la nature, mais de sa reproduction. Pour établir l'illusion, il faut que l'oeil, sur quelque point qu'il se porte, rencontre partout des figurations faites réels qui lui serviraient de comparaison; alors qu'il ne voit qu'une oeuvre d'art, il croit être en présence de la nature. Telle est la lois sur laquelle sont basés les principes de panorama.”

[52] Bapst cites an 1841 issue of César Daly’s Revue générale de l’architecture et travaux publics indicating that the roof should be conical. Also cited are the dimensions of Robert Barker’s first panoramas from the 1790s as well as one erected on the Boulevard Montmartre.

[53] Bapst, Essai sur l’histoire des panoramas et des dioramas, 10: “Les objets y doivent être répresentés d’après les règles de la perspective, en prenant comme point central la plate-forme où se tient le spectateur.”

[54] Alison Griffiths, Shivers Down Your Spine: Cinema, Museums, and the Immerisve View (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), 39, 43.

[55] “The Cyclorama,” Scientific American, November 6, 1886, 296.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Hermann Ritter, Perspectograph: Apparat zur mechanischen Herstellung der Perspective aus geometrischen Figuren sowie umgekehrt (Frankfurt-am-Main: Maubach, 1884); “Der Perspectograph von H. Ritter,” Centralblatt der Bauverwaltung, Vol. 4, No. 15 (12 April 1884), 139-140; “Ritter’s Perspectograph,” Scientific American Supplement, No. 451 (August 23, 1884), 7195-6; Édouard-Gaston Deville, Photographic Surveying, Including the Elements of Descriptive Geomtery and Perspective (Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau, 1895), 77-82, 98.

[58] Flemer, An Elementary Treatise on Phototopographic Methods, 298.

[59] Deville, Photographic Surveying, 223; Flemer, An Elementary Treatise on Phototopographic Methods, 296.

[60] Deville, Photographic Surveying, ix.

[61] See Sigmund Theodor Stein, “Photogrammetrie und Militaer-Photographie,” Das Licht im dienste wissenchaftlicher Forschung: Handbuch der Anwendung des Lichtes und der Photographie (Leipzig: Otto Spamer), 428-448. In the text, an image of a phtogrammetric survey of Vincennes (p. 437) appears alongside an engraving showing Prussian forces using photographic cameras during the siege of Strasbourg (p. 447).

[62] Aimé Girard, “Laussedat’s Arbeiten in Bezug auf die Anwendung der Photographie zur Aufnahme von Pläne,” Photographisches Archiv, Berichte über der Fortschritt der Photographie, Vol. 5 (1864), 316-322.

[63] Laussedat, “Notice sur l’histoire des applications de la perspective à la topographie et à la cartographie,” Paris-photographe, revue mensuelle illustrée de la photographie et de ses applications aux arts, aux sciences, at à la industrie, Vol. 1, No. 6 (Sept. 25, 1891), 263.

[64] Laussedat notes that the Comité had already been experimenting with cameras from 1851 until 1856. Recherches sur les instruments, les méthodes et le dessin topographique, 124.

[65] Laussedat, “Mémoire sur l’application de la photographie au lever des plans,” Memorial de l’officier du Génie our Recueil de mémoires expériences, observations, et procédeś généraux propres à perfectionner les fortifications et les constructions civiles et militaires, Vol. 17 (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1864), 252, n.2.

[66] Laussedat, Recherches sur les instruments, les méthodes et le dessin topographique, 124: “[U]n instrument destiné aux reconnaissances topographiques et accessoirement à la restitution des édifices, car nous n'avions pas oublié que notre première tentative faite avec le chambre claire, inspirée par l'exemple de Caristie, avait eu précisément pour objet de relever des mesures géométriques exactes sur une vue du dôme de Invalides, prise de la place Vauban.”

[67] Javary, “Mémoire sur les applications de la photographie aux arts militaires,” Memorial de l’officier du Génie our Recueil de mémoires expériences, observations, et procédeś généraux propres à perfectionner les fortifications et les constructions civiles et militaires, Vol. 22 (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1874), 394-5.

[68] J. Stolze, “Die Photogrammetrie,” Das Licht im dienste wissenchaftlicher Forschung: Handbuch der Anwendung des Lichtes und der Photographie, Vol. 5 (Leipzig: Wilhelm Knapp, 1887), 202, quoted in Laussedat, “Notice sur l’histoire des applications de la perspective à la topographie et à la cartographie,” 263, n.1.

[69] Mittheilungen über Gegenstände des Artillerie- und Genie-Wesens, Vol. 136 (1887), quoted in ibid., n.2.

[70] Laussedat, “Notice sur l’histoire des applications de la perspective à la topographie et à la cartographie,” 262-263.

[71] Laussedat, Recherches sur les instruments, les méthodes et les dessins topographiques, 125: “L'excellent opticien Bertaud jeune, qui, dès cette époque (1858), pratiquait très habilement une méthode des retouches locales, qui lui était propre, était parvenu à nous livrer un objectif simple dont le champ sans aberration sensible dépassait 30º.”; Flemer, An Elementary Treatise on Phototopographic Methods and Instruments, 6-7.

[72] Laussedat, Recherches sur les instruments, les méthodes et les dessins topographiques, 189.

[73] Flemer, An Elementary Treatise on Phototopographic Methods and Instruments, 6.